When the lavish, 26-room Barron Mansion went up in a blaze on Thanksgiving evening in 1936, firefighters from surrounding towns raced to unincorporated Barron Park to save the 80-year-old Victorian structure, which had just been converted into a school.

Palo Alto firefighters, who were stationed closest to the blaze, were the first to arrive, but rather than charge forth, they looked on from El Camino Real, about 100 feet away from the flames. The Palo Alto Times reported that the department had "refused to go beyond the city limits," pursuant to orders from the city's board of public safety. Residents of Barron Park, which had not yet been annexed to Palo Alto, had to summon firefighters and equipment from Menlo Park, Los Altos, Redwood City and the Moffett Field army air base. Firefighters tore down fences and positioned their engines near the school's swimming pool to ensure a water supply.

"Half a dozen streams were soon playing on the fire, under the direction of Chief Thomas Cuff of the Menlo Park department, but the blaze had already swept the dry and weathered old mansion from end to end," the Times reported.

The loss of Barron Mansion, and Palo Alto's conduct during the blaze, helped sour relations between the neighbors. Barron Park Historian Doug Graham recalled the incident in a 2005 newsletter, quoting a former Barron Park resident who had told him in the 1980s, "They only were there to keep the fire from spreading into Palo Alto -- they didn't give a damn what happened in Barron Park."

The Barron Mansion fire was by no means an isolated incident. The following August, a blaze at 2821 Waverley St. destroyed the new home of Mary Porter. Despite a valiant effort from neighbors, who pulled out everything but the piano and the stove, the flames quickly ate up the building. This time, no one bothered to call the Fire Department.

"None of the local fire department's units was summoned since Mrs. Porter's residence is outside the city limits," the Times reported.

These days, borders aren't what they used to be. Those that separated Palo Alto from the two burned structures have disappeared. Others have merely become more porous. Palo Alto began signing mutual-aid agreements in 1951, and it's not uncommon these days to see fire engines and police cruisers from neighboring towns routinely crossing city lines to assist their neighbors. Called "border drops," cities send their firefighting resources to incidents near the city line, regardless of the jurisdiction, said Dennis Burns, Palo Alto's police chief and interim fire chief.

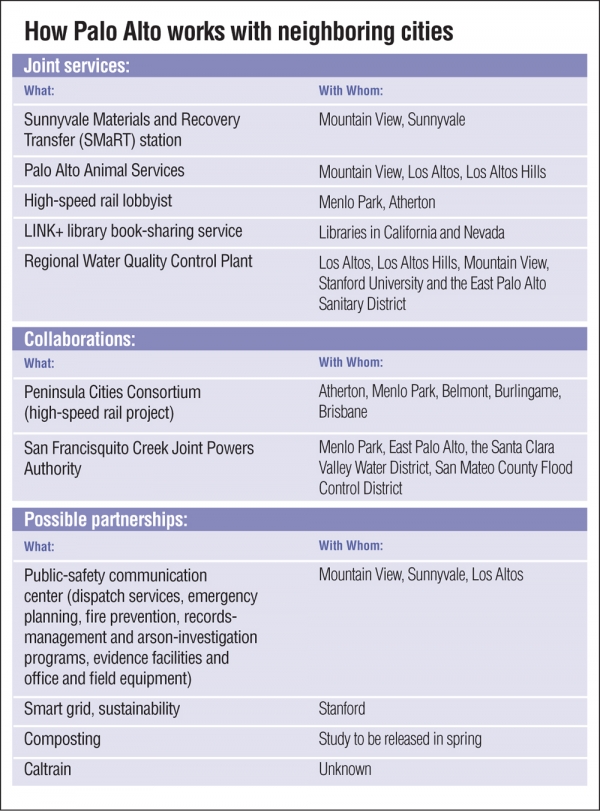

The trend isn't limited to firefighting or, for that matter, emergency response. Palo Alto is involved in partnerships with its neighbors in fields as dissimilar as water treatment, library books, garbage disposal, animal services and transportation planning. Palo Alto belongs to a six-city coalition dedicated to keeping up with California's high-speed rail project and a five-agency group tasked with protecting Palo Alto, East Palo Alto and Menlo Park from the flood-prone San Francisquito Creek.

While "Shop Local" may be the mantra of downtown Palo Alto merchants, city officials are thinking regionally more than ever before.

The trend is by no means new, but it has steamed ahead thanks to the Great Recession. With local tax revenues dropping, Palo Alto has been eliminating positions and reducing employee benefits to balance budgets. Over the past two years, the City Council has cut about 60 positions from the General Fund budget. Another 46 remain vacant to save money. At a recent council retreat, City Manager James Keene illustrated the current situation with a slide showing a slice of cheese full of holes -- each hole representing a major staffing vacancy.

At the same time, Palo Alto is preparing to deal with a host of problems, from the city's stalled quest for a seismically sound public-safety building to the impending closure of the city's composting facility to the implications of Caltrain's potential financial implosion. In each of these arenas, Palo Alto is banking on a little help from its friends.

Most of the work has been taking place behind the scenes, at routine meetings between city managers, law-enforcement agencies and waste managers. But on Jan. 18, Palo Alto's council publicly announced its desire to see more consolidation when it unanimously passed a resolution directing Keene to explore sharing a wide range of services -- including public-safety communications, emergency planning, fire prevention, records-management and arson-investigation programs, evidence facilities and office and field equipment -- with the cities of Mountain View, Sunnyvale and Los Altos.

The resolution, which passed with no discussion, also directs Keene to include funds in his next budget for a study of a joint public-safety communication center.

The resolution is "saying that we take the issue of more regionalization and sharing services seriously and it authorizes me to see if there are economies of scale or other advantages to doing that," Keene told the Weekly.

This was by no means the first time Keene has spoken publicly about the need to rely on neighbors to get through the lean times. Last June, when the council discussed the city's options for a new public-safety building, Keene spoke in favor of sharing resources.

"In general, we're in an era now where local governments, just as businesses have for a long time, are having to look at really different ways to organizing themselves and providing services," Keene said at a June 7 meeting. "We don't have the luxury of individually designed approaches to providing services when we don't have sufficient funding.

"I think increasingly we will see more efforts at looking at opportunity to share."

Since then, Keene has been at the center of these efforts. Last year, he regularly met with city managers Kevin Duggan and Doug Schmitz, from Mountain View and Los Altos, to discuss cities' upgrades of their respective dispatch equipment. The three city managers wanted to make sure they would upgrade to the same dispatch system so that each city could coordinate emergency calls across city lines.

During the course of the conversations, they started talking about full-on consolidation of dispatch services, fire-prevention programs, record management and other services to reduce overhead costs. Sunnyvale City Manager Gary Luebbers ultimately joined the discussions.

This week, the city released a new study by two consulting firms that analyzed the resources in the Fire Department. The consultant recommended that Palo Alto "regionalize the city's fire and EMS training program."

Mayor Sid Espinosa, one of the council's most adamant proponents of regionalization, credited the dismal economy for spurring these talks along.

"The recession is sparking conversations that I don't think would've happened without the pressures of cost-cutting," Espinosa told the Weekly. "I'm not sure the conversations between the city managers would've happened several years ago, but necessity calls for us to think outside the box and work with other jurisdictions to cut costs."

Espinosa likes to use the word "artificial" to describe city borders along the El Camino Real corridor. But not everyone wants to abandon those boundaries altogether.

Last summer, when the council's Finance Committee was wrestling with a $6.4 million hole in the city's Refuse Fund, then-Vice Mayor Espinosa suggested closing the city's Recycling Center in favor of a regional approach. The committee quickly shot down the idea.

Regionalization is already the norm in most areas of waste management. Palo Alto, Mountain View and Sunnyvale all ship their garbage to the Sunnyvale Materials and Recovery Transfer (SMaRT) station, where it gets sorted on conveyor belts, stripped of salvageable recyclable matter, and trucked to landfills. The SMaRT station also includes a recycling center where residents from all three cities are allowed to drop off materials at no charge.

But when it comes to composting, the drive to regionalize has encountered a wave of opposition from some of Palo Alto's greenest environmentalists.

The city's composting facility at Byxbee Park is set to close next year, after which time Palo Alto's yard trimmings and food scraps are set to go to the Z-Best station in Gilroy. Palo Alto's Zero Waste Operational Plan, which the council adopted in 2007, specifically recommends using a regional facility for local organic waste.

Many, however, feel Palo Alto should take care of its own yard waste, rather than ship it elsewhere. A coalition of environmentalists led by Bob Wenzlau and former Mayor Peter Drekmeier is leading a charge for a local solution to the composting problem.

In late 2009, a special taskforce recommended that the city explore building an "anaerobic digestion" plant -- a waste-to-energy facility that would convert local yard trimmings, food waste and sewer sludge into electricity.

Last April, after a four-hour debate featuring dozens of public speakers, the council voted 5-4 -- with Espinosa, Karen Holman, Greg Schmid and Yiaway Yeh dissenting -- to fund a feasibility study for a waste-to-energy plant in the Baylands.

Minutes later, the council voted on a separate motion, directing staff to pursue regional solutions for composting. The motion also passed by a 5-4 vote, with Pat Burt, Larry Klein, Nancy Shepherd and Gail Price dissenting (Greg Scharff voted in favor of both).

The feasibility study will be released in the spring, at which point the city's most passionate local vs. regional debate is likely to resume.

Other resource-sharing opportunities have proven less divisive. Last month, the council agreed to extend the city's participation in LINK+, a service the city joined in 2008 that allows local libraries to swap books with hundreds of others in California and Nevada. The program, which is projected to cost the city about $200,000 over the next two years, will give customers access to about 18 million volumes from dozens of libraries.

So far, only 0.7 percent of local library customers have used LINK+ -- a smaller rate than the city had projected. But library officials believe it will become more popular in the coming years and unanimously recommended renewing the city's participation.

The nonprofit group Friends of the Palo Alto Library also signaled its support for LINK+ and committed $100,000 to pay for the service.

Espinosa said as the city's budget woes continue, other opportunities for regional cooperation will almost certainly crop up. In some cases, this will involve sharing municipal services like emergency dispatch and record management. In others, it will entail forming partnerships with other communities to help influence state policy.

Palo Alto launched one such partnership in 2008, when former Councilwoman Yoriko Kishimoto helped co-found the Peninsula Cities Consortium to give the city and its neighbors a greater voice in California's high-speed rail system. The coalition now includes elected leaders from Atherton, Menlo Park, Belmont, Burlingame and Brisbane. The city also shares a high-speed-rail lobbyist with Menlo Park and Atherton and has joined its two Midpeninsula neighbors in a lawsuit against the California High-Speed Rail Authority.

The challenges of a new year are expected to present cities with other opportunities to team up. One major area of potential cooperation lies in securing permanent funding for Caltrain, Espinosa said. Another one is finding a way to meet stringent state mandates requiring each community to zone for its "fair share" of housing (in Palo Alto's case, city officials agree that the "fair share" is neither fair nor possible).

In his view, thinking regionally isn't so much an option on these issues but a necessity.

"There are specific issues where communities will have to come together to come up with solutions," Espinosa said.

Related stories:

Comments

another community

on Feb 4, 2011 at 1:41 pm

on Feb 4, 2011 at 1:41 pm

Step One in a decision to merge one city's services with another is to ask if each community is functioning reasonably well to begin with. Palo Alto's neighboring communties are indeed functioning well. But it does not take a brain surgeon to know Palo Alto is a disaster, in every area of city government, & it must be isolated.

While neighboring communities can be good neighbors with Palo Alto, helping out in emergencies, no City Managers should think of merging anything officially with Palo Alto, without first counting the great costs. It is just not worth it. Please - no mergers of reasonably healthy communities with Palo Alto.

Another Palo Alto neighborhood

on Feb 5, 2011 at 3:44 pm

on Feb 5, 2011 at 3:44 pm

The previous poster makes a number of assertions about the financial wellbeing of the surrounding cities (around Palo Alto), but does not provide much proof. Menlo Park just went through an election to decrease their pension multiplier from whatever it was to 2.0% (which will save the taxpayers millions downstream). Palo Alto was able to do the same thing at the Council level without an election. San Jose has recently become aware that it has a (perhaps) $2B unfunded pension liability, whereas Palo Alto does not seem to be in as bad a situation. As to the unfunded pension liabilities of the "sister" cities, there hasn't been as much discussion of this problem as in the larger cities. So, no one knows other than the finance people for each of the municipalities what their situation is.

So .. the claim that Palo Alto is "bad" and the rest are "good" needs to be taken with a grain of salt. Given that virtually every City has the same problem: seemingly out-of-control labor unions demanding ever high salaries, and benefits .. all of us are in the same boat ..

The issue on the table is: "how many redundancies exist across the regional governments that could be reduced by a merging of services, that would otherwise just increase in cost over the coming years without actually providing any increased value added to the taxpayers to justify the increase cost?"

For instance--how many IT departments does Palo Alto, Menlo Park, Los Altos, Los Altos Hills and Mountain View need? Could one do the job? Same question for Human Resource departments, or park departments .. and so on. And the same question goes for public safety services.

What's needed is to put all of the budgets on the table, and project the costs forward twenty years; then, reorganize and do the same projection. The difference in costs becomes the reason for considering this sort of merger.

Just talking about it, or listening to people who are happy with their cushy jobs .. isn't going to get the necessary preparatory work done that is needed to be able to see if this sort of thing makes sense or not.

Time for the local City Managers to "step up" and get this process started.

Triple El

on Feb 7, 2011 at 2:04 pm

on Feb 7, 2011 at 2:04 pm

Seems to me as the previous poster glosses over is the liability for payment of benefits and retirement to employees for agencies that merge. What if a city or government agency disputes the amount they consider their fair share or have an "off" year or as Palo Alto managers claim every year they are bankrupt, (never mind they have $300,000,000* in various reserve funds) Guess thats what lawyers are for. As the reporter points out, agencies already cross city lines as evident in the number of Palo Alto fire vehicles parked at Mtn. View Safeway daily.