• To read about what's driving Palo Alto's growing payroll, click here.

Click on the links below to read about each group's employee compensation:

• Service Employees International Union, Local 521

• Management and Professional group

For Palo Alto police officers and firefighters, change in compensation can't come soon enough.

The salaries of the city's public-safety employees have been largely frozen since the economic downturn, even as their contributions toward their pensions and health care have gone up. Both the Palo Alto Police Officers Association (PAPOA) and the International Association of Fire Fighters, Local 1319, are now in negotiations with the city over new contracts.

If recent history is an indicator, the period of salary stagnation for local police officers and firefighters should come to an end in the coming months. The question is no longer whether they will get raises, but how high these raises will be.

Both management and unions agree that salaries need to be high enough to recruit quality employees and retain the existing workforce, the same principle that guided negotiations with the SEIU and the management group. In April 2012, the Palo Alto City Council adopted a set of principles to guide labor negotiations, one of which included compensation at a level "sufficient to recruit, train and retain qualified employees who are committed to the City's goals, programs and delivery of high-quality services." Another calls for "equity across employee groups" and directs the city to "strive to set and make similar structural changes to compensation and benefits for all employee groups, while recognizing that some flexibility may be required to fully address issues specific to individual units and/or achieve the objectives of other guidance principles," when economically feasible.

Both of these are now coming into play as City Manager James Keene and the City Council are moving toward new contracts with the city's two largest public-safety unions.

For the firefighters, a new contract promises a welcome departure from recent bleak years. No single labor group has suffered as many gut punches during and since the recession, with wages static and benefits cut back.

In 2010, the union rolled the dice when it placed on the ballot an initiative that would require a vote of the electorate any time the city wanted to reduce Fire Department staffing or close a fire station. With the council and most community leaders taking a stand against Measure R, the proposal went down in flames, with about 75 percent of the voters rejecting it. The following year, the union suffered another stinging defeat at the ballot box when voters approved Measure D, which removed a "binding arbitration" provision from the City Charter. The long-standing provision empowered a panel to arbitrate contract disputes between management and firefighters, who unlike most other workers are legally barred from striking.

Just weeks before the 2011 election, the city and the union concluded a 16-month marathon of negotiations by reaching a three-year deal that forced firefighters to contribute toward their pensions. More significantly, perhaps, the contract eliminated a long-standing "minimum staffing" provision that required at least 29 firefighters to be on duty at all times and which had resulted in sizable overtime pay.

Fire Captain Ryan Stoddard, the union's recently elected president, estimates that the 2011 changes to the union's benefits reduced the total compensation of firefighters by about 12 percent. The goal in the current negotiations is to return to pre-2011 compensation.

"With the economy doing as well as it is, our biggest priority is trying to get to where we were when we took that hit," Stoddard said. "We're trying to get back to the starting point, to make even with what we had."

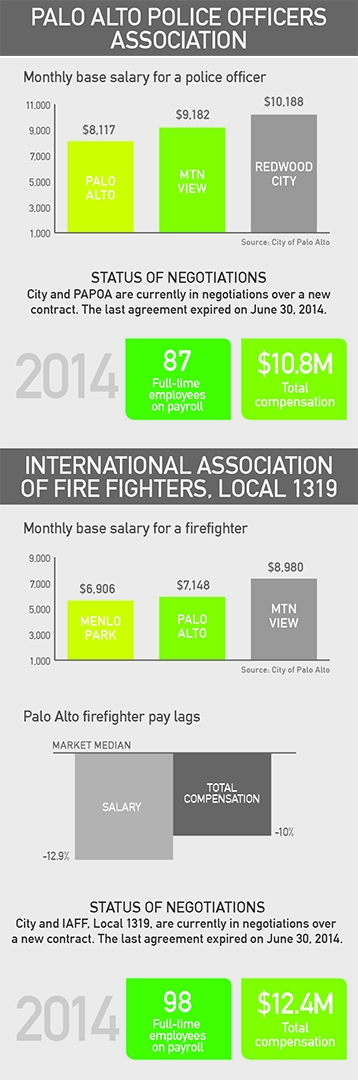

If the city's goal is to bring local salaries in line with the median average (as it did with other employee groups), the firefighters have a strong case. As part of the negotiations, the city and the firefighters union have each commissioned a study comparing the salaries of local firefighters to those in other jurisdictions. The two studies reach the same conclusion: Palo Alto firefighters make at least 10 percent less than the median. For a typical firefighter, the monthly base salary in Palo Alto is $7,148 (12.9 percent below the median), compared to $8,980 in Mountain View and $9,834 in Santa Clara, according to the city's analysis. Of the 15 jurisdictions surveyed by the city, only Menlo Park and San Ramon Valley firefighters made less than Palo Alto's.

When benefits are added to the mix, a Palo Alto firefighter's compensation goes up to $11,477, which is still 10 percent below the median. Other positions in Palo Alto's department — including fire-apparatus operator, paramedic and fire captain — likewise come with smaller salaries and are around 10 percent below the market median after factoring in benefits.

The difference is less drastic on the police side. Both the police union's study and the city's suggest that local police salaries are below market. The city's analysis shows a Palo Alto police officer's salary to be about 8.1 percent short of the median. Yet when benefits and retiree medical costs are added in, the total compensation in Palo Alto becomes roughly equal to the median.

The union's analysis concluded that Palo Alto officers get total net compensation (which includes salary, bonuses, health care benefits and employee contributions) 9.5 percent below the regional median. It also noted that other area departments, including those in Mountain View, Santa Clara, Sunnyvale and San Mateo, typically offer a 5 percent premium to investigators and officers in other specialized positions. Palo Alto does not.

Unlike the firefighters, the police union's relationship with management has been comparably amicable, even through difficult financial times. In 2009, the union agreed to defer its negotiated 6 percent raise for a year to help the city balance the budget. Two years later, while the firefighters were up in arms about the city's effort to repeal binding arbitration, the police officers remained relatively quiet, even though the provision applied to police just as it did to firefighters.

But when the city began talking about changing health care benefits for future police retirees, the period of peace came to an end. In 2012, both PAPOA and the small union of police managers rejected the city's request that new retirees foot 10 percent of their health care costs. The contract that the city ultimately adopted in 2012 with the larger police union included a salary reduction of 1.3 percent and an impasse on the issue of health care. PAPOA requested a fact-finding procedure to resolve this dispute, as provided for by a 2011 state law that empowers a panel to consider the issue leading to an impasse and make recommendations.

For both the police and the firefighter unions, the issue is clear: The city made a pact with its employees at the time they retired and is now trying to tap into their vested rights.

During hearings in front of the fact-finding panel, numerous officers testified that they had forgone positions in other departments because of assurances that their medical costs would be covered in retirement — a provision that former Police Chief Lynne Johnson referred to as "golden handcuffs."

Former union president Sgt. Wayne Benitez said that he was planning to switch to the Sonoma County Sheriff's Office five years ago but was persuaded to stay by his lieutenant, who told him, "You cannot walk away from lifetime medical," according to the report from the fact-finding panel. Capt. Ron Watson, who now heads the seven-member union for police managers, testified that "he never set aside any funds for health care costs in retirement in reliance on what he had been told about his benefit program and that now, as he approaches retirement age, he is being forced to 'scramble' to set aside sufficient funds to secure full health coverage for himself and his family."

Firefighters also have a vested interest in this argument. Stoddard told the Weekly that the retiree benefit has always been a major incentive for people who have chosen the Palo Alto Fire Department over other agencies.

"We're open to having conversations on how to redevelop our health plans, especially with active employees," Stoddard said. "It's more tricky when you're talking about retired employees."

The benefit also helps explain why public-safety employees are willing to accept Palo Alto's lower salaries, he said.

"Over the course of our history, we have chosen to take smaller wage increases so that we can keep a higher health benefit. Our members took a lower wage but received better retirement and pension plans."

For the city the issue is also clear. Other employee groups have accepted the benefit reductions, and getting the police union on board is both the fair thing to do and financially prudent.

"It is not acceptable to push risk-sharing off to future generations of employees or to ask the city's taxpayers, who have important interests in ensuring that the city has the resources to continue to fund the services and infrastructure that make Palo Alto a desirable place to live, to shoulder the entire burden on an expensive benefit," City Attorney Molly Stump argued in the city's closing brief.

The panel struggled for two years to resolve the stalemate between the police union and the city. Its pages are laced with frustration and exasperation as it chides both sides for "inexplicable delays, a hardening of both parties' positions and a lack of creative collaboration." The argument, the panel found, has "degenerated into a vortex of points and counterpoints."

The union proposed maintaining retirement benefits for all active employees and creating a less generous plan for new hires: Anyone hired after Aug. 1, 2012, would only get retiree health care benefits after 20 years of service, a benefit that would not extend to dependents.

In the end, the panel concluded that both proposals would likely damage employee morale but called the city's plan the "less undesirable of the two options."

Keene said he expects that once the retiree-benefit portion of the dispute is resolved, management will be able to reach an agreement with its public-safety employees on the other issues.

Officer Jeremy Schmidt, president of PAPOA, declined to discuss the matter because the union is actively negotiating.

"What I can tell you is that we always strive for the best possible combination of pay and benefits to attract and retain the high caliber employees the citizens of Palo Alto deserve," Schmidt said in an email.

Like the unions, Keene said the city is concerned about recruiting challenges and committed to attracting good talent to the organization. The problem, he said, is that given the current trends, the city simply can't afford to maintain its traditionally generous benefit packages.

Take pensions, for example. In fiscal year 2014, the city's spending on the pensions of public-safety employees were equivalent to about 33 percent of employee salaries. Based on the information that the city received from CalPERS, the state's giant public-pension fund, that proportion could climb to as high as 50 percent by fiscal year 2019.

"Some of the discussion is driven by the fact that our costs are going to increase — particularly on the benefit side of things," Keene told the Weekly. "The increasing costs on the pension side are really kind of dictating our approach in negotiations with the different employee groups about what we would be offering."

It's not unusual in negotiations for each side to kick off the proceedings by shooting for the moon and then gradually and painstakingly move toward a more realistic compromise. Even so, a look at the preliminary offers and counter-offers between the city and the firefighters union suggests that the starting points aren't in the same galaxy, much less ballpark.

In June, the firefighters proposed a three-year contract with a 15 percent raise in the first year and 10 percent raises in the second and third years, according to documents obtained by the Weekly. In October, the city offered the firefighters a 2 percent raise in exchange for various adjustments to pension and health care benefits, including a switch from having the city's contributions be a percentage of the premium to having it be a flat fee.

When asked about the status of the negotiations, Keene said there is a "really big gap between where the city and the firefighters are" and a "lesser gap on where the city is with PAPOA."

The newly reconstituted City Council is just starting to delve into this topic. The council received a refresher course on the complex topic in a closed session earlier this month, a discussion that stretched from 11 p.m. to 1:20 a.m., according to the city. The council picked up where it left off with another closed session this past Monday, just before its regular council meeting.

The negotiations are complicated by the two seemingly contradictory directives: to attract quality workers and to contain long-term costs. The city wants to add more workers to meet the increasing demand yet keep the workforce small enough to prevent a further ballooning of long-term cost obligations. Hopefully, Keene said, the city "can reach a point that's workable for everybody."

"Even though the economy is doing better and the city's finances are better, we really have to be wary of the long-term implications of the pay and benefits that we offer, even when we're just trying to stay competitive in the marketplace," Keene said. "We can't turn a blind eye to the fact that pension costs and health care costs can increase over time and generate real problems for us in the future."

Comments

Community Center

on Apr 24, 2015 at 8:50 am

on Apr 24, 2015 at 8:50 am

There is an interesting theme here.

Why is it every couple years when these issues come up, the police union is acting and being professional and the fire department is always the problem.

Outsource fire to the county or the state. Keep the paramedics which are a smaller fraction of the department. We will still get the service at a much lower cost.

Midtown

on Apr 24, 2015 at 11:40 am

on Apr 24, 2015 at 11:40 am

I'm sure the fire department would love to merge with County fire department. They would get a 35+ % raise! The Palo Alto fire department is one of the lowest paid departments in the bay area and the cheapest to run.