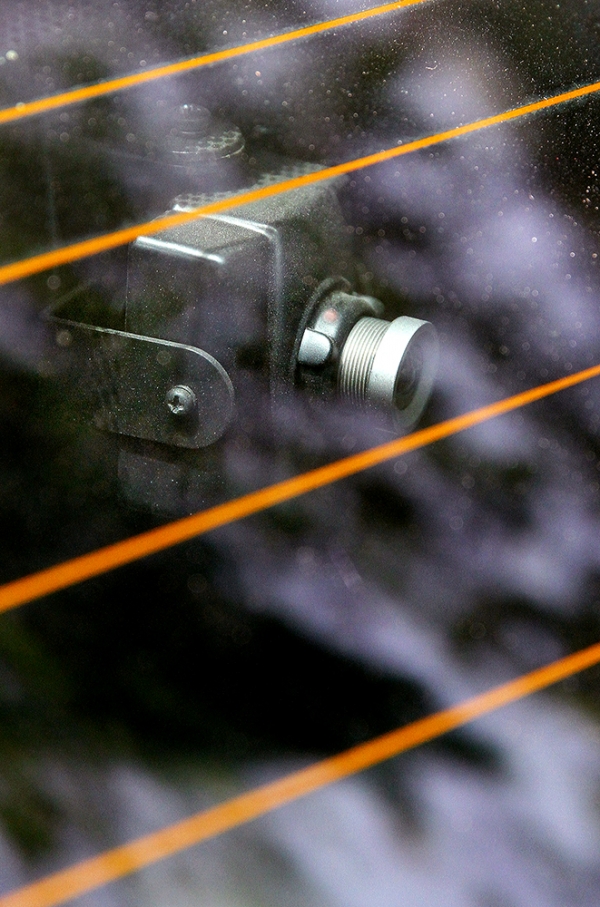

A police cruiser in Palo Alto has five cameras: one pointing toward the front, another toward the rear, two covering the blind spots and one fixed on the passenger in the back.

When the cruiser is on, the five cameras are almost always rolling; when they roll, they cover everything within a 270-degree radius. They can also allow officers to peer into the past: Up to 40 hours of recent footage, going back to the moment the ignition is turned on, is saved.

In a presentation to the city's Human Relations Commission, police Lt. Zach Perron lauded the new technology and said that he gets inquiries about it from other police departments nearly every week.

"It's remarkable," Perron told the commission. "We're really the only department around here that has anything like this."

The cutting-edge camera systems are emblematic of the department's, and more broadly the city's, enthusiastic embrace of the latest and greatest in surveillance technology. In addition to the in-car camera system implemented in 2007 — known as MAV (Mobile Audio/Video) — the Palo Alto Police Department began in 2014 to equip its officers on motorcycles and bicycles with body-worn cameras. And in 2013, the city acquired an automatic-license-plate reader, a device that gets mounted on a police vehicle and uses small high-speed cameras to scan and photograph plates, with the goals of identifying stolen vehicles, locating suspects or recovering stolen property.

The proliferation of cameras isn't new, but it's expected to intensify in the years to come. Police Chief Dennis Burns told the Weekly that in the coming month or so, the department plans to roll out a new version of the body-worn camera. After a trial period, these could become standard equipment for all sworn officers. Made by WatchGuard Video, the manufacturer of the city's new in-car cameras, the new body-worn cameras are able to sync up with the MAV systems. Instead of a five cameras per cruiser, there would be at least six.

Body cameras are becoming a new normal in municipalities across the Bay Area, with San Francisco, Oakland and Alameda County all adopting them in recent years. But even though Palo Alto officers have been using body-worn cameras for nearly two years now, the department doesn't have an official policy in place to govern them. Rather, it relies on an interim policy that was drafted in 2014, is only half a page long, gives officers full discretion (and little guidance) in deciding when to turn the body-worn cameras on or off and expressly states that "no officer will be counseled or disciplined for failing to use or activate a body-worn camera during the trial or testing period."

Burns said the department plans to adopt an official policy for body-worn cameras later this year, after public meetings, City Council feedback and the department's trial of 10 new body cameras. If they work out, the department will get about 80 more, enough to equip every sworn officer.

The tendency of policy to lag behind technology is nothing new when it comes to body-worn cameras, automatic license-plate readers, drones and other investigative tools. Nor is it limited to Palo Alto. In May 2015 a special task force on policing established by President Barack Obama released a report that states the problem succinctly: "We live in a time when technology and its many uses are advancing far more quickly than are policies and laws."

The report makes a case for body-worn cameras and cites a 2014 study published in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology that found that officers wearing cameras had 87.5 percent fewer incidents of use of force and 59 percent fewer complaints than officers not wearing the cameras. Yet the study also warns that without adequate public outreach, the new technology can spark distrust when it comes to privacy. When the public does not believe its privacy is protected, the report states, "a breakdown in community trust can occur."

"Agencies need to consider ways to involve the public in discussions related to the protection of their privacy and civil liberties prior to implementing new technology, as well as work with the public and other partners in the justice system to develop appropriate policies and procedures for use," the report states.

To date, Bay Area law-enforcement agencies have generally taken a better-to-ask-for-forgiveness-than-permission approach to their surveillance purchases. In San Jose, the police department caused a public outcry last year for buying a drone without notifying the public. After a flurry of criticism from residents and civil-liberty advocates, the city hosted a series of meetings about the new technology, and the City Council adopted in August a new policy specifying that the drone would only be used in two situations: to assist the bomb squad and when there is an active shooter.

Similar concerns dogged an effort by Santa Clara County officials to buy a Stingray, a device that intercepts cell-phone data by essentially masquerading as a cell tower. Last year, the county abruptly canceled its plan to buy a Stingray after the manufacturer demanded a non-disclosure rule. Now, county Supervisor Joe Simitian is leading an effort to craft an overarching policy on surveillance technology that would require county departments to submit an "anticipated impact report" before they deploy new surveillance technology; adopt policies for the technology before they acquire and use it; and provide periodic reports describing how the technology was actually used. The board's Finance and Government Oversight Committee signed off on the policy on April 14, and the full board is set to consider it next month.

This week, Palo Alto moved ahead with a similar effort. Four council members, led by Councilman Cory Wolbach, recently penned a memo calling for the city to draft an ordinance that would establish a "standard operating procedure" for adopting or re-purposing any technology for surveillance.

The memo, which is co-signed by Vice Mayor Greg Scharff and councilmen Marc Berman and Greg Schmid, lists the various technologies already in place in Palo Alto and notes that both law enforcement and government in general "depend on the trust of the community."

"Use of technologies (that) has the appearance, potential or effect of violating privacy or civil liberties can diminish community trust in government, particularly when adopted and used without transparency. ... Rapidly evolving surveillance technology raises concerns for the City including, but not limited to privacy of residents and visitors; chilling effects on expression, research, travel, association or other rights; misuse of data; data breach (access by unauthorized parties); and adoption, use or expansion of capabilities without council oversight."

Wolbach told the Weekly that the move is intended as a "proactive" step to prevent future uproar, like the one in San Jose over the drone or the one at the county level over the Stingray.

"We've seen times when things like this have been deployed without a lot of oversight and without public transparency," Wolbach said. "That's where you have concerns. That's one of the main things we want to avoid. We just want to make sure the council and community feel comfortable and have an insight into what types of technologies we're using as a city and also make sure that the technologies we do desire are appropriate and we're using them in an appropriate way."

When it comes to body-worn cameras, the council's oversight has to date been minimal at best. Last June, the council unanimously approved a Fiscal Year 2016 budget that included $95,000 for 90 body-worn cameras. When the council's Finance Committee reviewed the budget request, only one council member — Councilwoman Liz Kniss — asked a question about the cameras (and the question pertained to the protocol for budgeting, not the merits of the technology). When the annual budget went to full council for approval, the subject of body-worn cameras wasn't broached at all. It's taken as gospel at City Hall that — privacy concerns notwithstanding — body-worn cameras are a valuable tool for collecting evidence and making police officers more accountable to the public.

The cameras in action

In describing the merits of surveillance cameras, Burns told the Human Relations Commission last June they have three chief benefits: They collect great evidence. They insulate the department against false claims. And they foster accountability among officers.

"Everybody plays a little better when they know the camera is on," Burns said.

And the case for body cameras specifically? Between 40 and 60 percent of the interactions officers have with the public are not in front of a patrol car, Burns noted.

Yet body-worn cameras are useful only when they're on. That was not the case last November, when Stanislav Petrov was chased down and tackled by an Alameda County sheriff's deputy in an alleyway in San Francisco's Mission District after a high-speed pursuit. Footage from a surveillance camera in the alleyway shows two deputies repeatedly beat Petrov with batons for about 20 seconds while he was lying on the ground, before more officers arrived. Though all 11 officers were equipped with body-worn cameras, none reportedly used them. The department, which is now facing a lawsuit from Petrov, has since revised its policy to make use of body-worn cameras mandatory.

Questions about when the recording system should be used aren't limited to Alameda. In Denver, a six-month pilot program in late 2014 showed that out of 45 use-of-force incidents that involved officers with body cameras, usable footage was available for just 21 incidents. Nicholas Mitchell, police monitor for the Denver police and sheriff's departments, found that in 11 of these 45 cases, officers reported that the encounters "progressed or deteriorated too quickly for them to safely activate the BWC." In other cases, they reported that they either failed to charge their units, could not download footage, or wore the cameras in a way that obscured the audio and/or video, according to Mitchell's report.

In Palo Alto, a failure to record a use-of-force incident proved costly in 2013, when officers arrested Tyler Harney, a Los Altos Hill resident, after a traffic stop. Harney, who filed a federal lawsuit against the city in 2014, alleged that during the traffic stop officers slammed him into a car and injured his arm and shoulder. He also claimed that he was convulsing from a seizure when officers brought him to the ground and pulled his arms behind his back to handcuff him. The in-car camera system (the prior model that was about to be replaced) malfunctioned and the incident was not recorded.

Even though city officials denied that officers used excessive force, in March the council approved a $250,000 settlement with Harney. When asked about the settlement, Mayor Pat Burt told the Weekly that not having the footage was a "disadvantage on defending ourselves." Thus, the council thought it would be prudent to settle.

By and large, Palo Alto officials have relied on police cameras while investigating a range of incidents, from violence to citizen complaints. Most recently, the department reviewed footage from multiple cruiser cameras after Palo Alto officers fatally shot 31-year-old William Raff in front of a group home on Forest Avenue last Christmas — its first fatal incident in more than a decade.

According to the police (who have declined to release the video to the public), footage allegedly showed that Raff had a knife and sprinted at the officers, getting so close that "one officer who fired his pistol had to move to avoid being struck by the falling suspect." The video footage, as well as witness testimony and other evidence, has been turned over to the Santa Clara County District Attorney, who is reviewing the incident.

In other cases, the footage has served as an arbitrator between an officer and a citizen making a complaint. Consider, for example, an incident in 2010 when a 70-year-old woman accused officers of injuring her ribs while using excessive force to arrest her.

The city's Independent Police Auditor Michael Gennaco reviewed the complaint and, in doing so, went to the tape. The footage, according to his report, showed the officer pulling over a woman after she ran a red light. He talked to her for a few minutes while she was in her vehicle. He walked back to the cruiser. The woman then started to get agitated. She got out of her car and started walking toward the officer and his partner. She yelled, slapped her fists against her torso and, according to the audit, briefly took a "martial arts stance." When officers attempted to restrain her by pressing her against the side of the car, she tried to bite the female officer before she was taken slowly to the ground, handcuffed and walked back to the sidewalk.

The auditor noted in the report during the initial interaction, the officer appeared to adopt a "patient and calm demeanor." And even though the woman was 70 at the time of the incident, "she appears to be equal in stature to the officers and does not appear frail," the auditor wrote. He concluded that the officers appeared to show "restraint and consideration" and noted that they took pains not to injure her. His verdict? No excessive force.

At other times, the video evidence revealed officers doing things they shouldn't. This includes an incident in early 2013 in which a citizen called the station to complain about a rude officer. Footage from the incident, which the police auditor reviewed, reportedly showed a man and a woman preparing to cross the street when the police cruiser stopped several feet into the intersection. When the man raised his hands in a "what the heck" gesture and said something about the crosswalk, the officer shouted back a profanity, according to the auditor. The officer then rushed off, failed to stop at two stop signs and, according to Gennaco, violated "the right of way of other cars by making a left turn."

In some cases, the cameras capture footage that officers' eyes can't see. That's what happened in late 2014, when two suspects — a man who was arrested for probation violation and a woman who was nabbed for an assault at a bar — were being transported to jail in the same cruiser. According to Gennaco's report, camera footage showed that during the ride to the jail, the man repeatedly slid closer to the woman and touched her breast with his elbow. The woman, according to Gennaco, repeatedly admonished the male to stop touching her and tried to get help from the officers (at one point she was reportedly heard saying, "That's sexual harassment. Hey, this guy is touching me"). The officer, who was listening to music on the radio during the trip, took no action apart from "a few spoken directions" to the man, Gennaco reported.

After they arrived at the jail and the woman repeated her complaint, police reviewed the footage and charged the man with battery, of which he was later convicted.

While there is nothing controversial about a camera running inside a police cruiser, where there is little expectation of privacy, things are less clear-cut when it comes to body-worn cameras. In one incident, which occurred in late 2014, an officer with a body-worn camera pulled over a woman for speeding while she was on her way to an urgent-care facility. He then reportedly directed her to leave her car in the facility's driveway and followed her inside. As she was waiting to get treated, Gennaco wrote, the officer asked urgent-care personnel if she had time to move her car, given that it was parked illegally. He then asked the woman to do so and gave her a speeding ticket.

The woman later complained that the officer, by following her inside, delayed her medical treatment — an argument that both the police department and Gennaco rejected. But the auditor also noticed, in reviewing the footage, that while the woman was describing her symptoms to the receptionist "it is clear that the officer was close enough to overhear the conversation."

Gennaco concluded that in this case it was "improvident and unnecessary for the officer to stand by the female while she described her medical condition to a medical-care provider," especially given that medical information is protected by state and federal law.

"His presence likely contributed to her distress and her unhappiness over the way he handled the situation," Gennaco concluded. "It would have been helpful had PAPD supervision identified this particular issue and informally raised the matter with the officer; the officer may have benefited from additional insight into the complainant's perspective."

After his review, Gennaco recommended that the department remind its members to avoid listening in when individuals are providing medical information to medical practitioners. He also recommended that the department consider providing written guidance to officers "regarding the deactivation of body-worn cameras when medical information is being shared between a health care provider and a patient."

Burns said situations like these — when an officer with a body-worn camera enters a private residence or when an individual is describing his or her medical condition — are ones that the department will be evaluating with the community in the coming months.

"One of the important things to remember is that we only want to capture the information that is relevant to whatever we are investigating," Burns said. "We have to be very careful about what we're going to record when we go inside someone's house, and it's going to depend on the nature of the call, what information we have and so on.

"Similarly, we have to think about whether we should be turning off a recorder when we're in an action scene and people are injured — out of respect for people who are injured and to make sure we don't capture on video any information that would be covered under HIPAA," he added, referring to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which protects individuals' medical information.

County considers new policy, too

While the Palo Alto Police Department is preparing for a public conversation about body-worn cameras, both the City Council and the county's Board of Supervisors are delving into policies that are far broader in scope.

Simitian, who has been working on privacy-rights issues for more than 15 years (he chaired a committee on the topic as both a state Assembly member and state Senator), is leading the charge on the county level. In recent months, as chair of the board's Finance and Government Oversight Committee, he's been soliciting input from the offices of the District Attorney, the Sheriff, the General Counsel and other stakeholders about the new policy, which would govern both existing and future surveillance technology.

For Simitian, this issue came to a head during a tense Feb. 25, 2015, hearing when he questioned Sheriff Laurie Smith about the purchase of a Stingray and was visibly frustrated with the vague answers he received about the new technology. After a long exchange, Simitian concluded that the board didn't have nearly enough information to justify the purchase.

"Just to be clear, we're being asked to spend $500,000 of the taxpayers money, plus $42,000 a year thereafter for a product the name of which we're not sure of, the product specs we haven't seen, a demonstration we don't have, and we've got a non-disclosure requirement as a precondition. ... So you want us to vote to spend money on something that you can't tell us more about."

The board approved the purchase 4 to 1, with Simitian dissenting, but the purchase was ultimately scuttled after county executives decided that the non-disclosure policy demanded by the manufacturer was too restrictive. Since then, Simitian and Supervisor Cindy Chavez have been moving ahead with a broader policy to govern all surveillance technology, which would list specific technology and describe the characteristics of future technology that would be governed.

There's been some pushback. Michael Whittington, president of the Santa Clara County District Attorneys Investigators Association, told the committee on April 14 that the union objects to the new ordinance because of its lack of specificity in defining "surveillance" and because of the "onerous amount of work" the new rules would create for his investigators.

"As written, everything would be surveillance and require documentation as the process is going on, which would slow down our investigators and slow down investigations and cause an undue adverse burden to labor," Whittington said.

But most of the speakers at recent hearings concurred with Simitian that the policy would be valuable. Andrew Gutierrez, representing the county Public Defender's office, observed that we live "at a time when government agencies are collecting increasingly vast amounts of digital and/or electronic information.

"Much of that information can be tied to a particular individual," Gutierrez said. "The ability to store such information is likewise increasing dramatically. The fact that local government agencies can collect and retain such a vast amount of data creates serious privacy and civil-liberty concerns."

After months of refinements and edits, the committee voted on April 14 to send the proposed ordinance to the full board, which will consider it in May. Simitian stressed at the meeting that the new ordinance will not prohibit the use of any surveillance technology. It would, however, create a process for how such technology is adopted. This includes an "anticipated impact report" before the item is purchased; a set of policies to govern the use of the device; and an annual report detailing how the devices had been used.

"It's been a grueling process, and I think one of the things that we've had to work our way through and past is the misperception that there is an inherent trade-off between privacy and public safety," Simitian told the Weekly. "I reject this notion outright. I think we can protect the public while still respecting the public's right to privacy and due process."

On Monday, Palo Alto began its consideration of similar guidelines when the council voted 7-0 (with Liz Kniss and Eric Filseth absent) to have its Policy and Services Committee craft a "standard operating procedure" for new surveillance technologies, which would ultimately be referred to the full council. In introducing the item, Wolbach said he is particularly concerned about policies governing collection, retention and dissemination of data.

"We could be trying to respond ad hoc to each new technology as it arises, but as co-authors of this memo, we are of the opinion that we should be proactive," Wolbach said.

The council largely concurred, with Berman arguing that it's best to "have a policy in place before you have a problem" and Scharff encouraging his colleagues to focus on technologies that are capable of personally identifying individuals.

The council also heard from several speakers, including privacy and civil-liberties advocates, all of whom heartily endorsed moving forward with the ordinance. Adam Schwartz, a civil-liberties attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, observed that new technologies are "changing people's lives."

"Obviously they can do a lot of good; they can make our government more accountable and more efficient," he said. "Sometimes, these technologies can diminish our privacy and civil liberties and even chill our free speech. Without trust between community and police there can be no public safety. We think this kind of policy will do a great deal to advance trust."

Paul George, director of the Peace and Justice Center in Palo Alto, agreed. He told the council that a public discussion about technology before it's adopted is an "absolute must in a democratic society." The increased workload in putting the reports together, he said, is a small price that a "free democratic society must pay to remain free and open."

Unlike at the county level, the Palo Alto proposal so far has the full support of the city's top law enforcement official. Burns told the council Monday that he believes that "having the conversation in advance, establishing the values of the community and setting standards is very prudent" and recommended sending the item to the committee for further discussion. In a recent interview with the Weekly, he said he looks forward to the community conversation and stressed that, when it comes to in-car cameras, body-worn cameras and other forms of surveillance equipment, Palo Alto officers focus solely on data that pertains to the calls they are responding to.

"As far as surveillance goes, we're busy enough just trying to investigate and respond to the calls that we have," Burns said. "We have no interest in gathering any greater data for any other reason. Frankly, it's not in our mission and it's not in our purview and, therefore, we shouldn't be concerned about things that aren't directly related to what we have before us — be it a crime or be it a mental-health issue or what have you."

Comments

Downtown North

on Apr 29, 2016 at 9:06 am

on Apr 29, 2016 at 9:06 am

I really like the story about the "patient and calm" officer on the traffic stop. I witnessed this incident and am not afraid to share that it was in fact Officer Amadeo. He is the most amazing officer Palo Alto has for sure. so run and tell that.

Downtown North

on Apr 29, 2016 at 11:26 am

on Apr 29, 2016 at 11:26 am

The research and policy development of the NYPD might be helpful to obtain. They may

be more advanced in their training and experience; and if so, the Palo Alto process could be

be expedited.

College Terrace

on May 16, 2016 at 10:48 am

on May 16, 2016 at 10:48 am

Nice...but what about that California public law that protects the 14th ammendent privacy rights ??

You know....... voice recordings...without permission...even on videotapes are deemed ILLEGAL & in violation