On a single block of Webster Street in the Old Palo Alto neighborhood, a tale of two basements is unfolding — one that illustrates the city's evolving debate over groundwater.

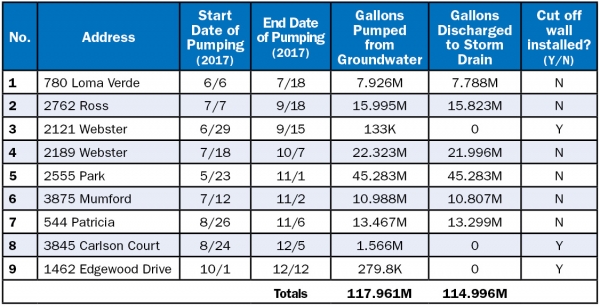

At 2189 Webster St., near North California Avenue, contractors building a basement began pumping water out of the ground on July 18, according to data obtained by the Weekly. By the time the pumping concluded on Oct. 7, they had extracted 22.3 million gallons of groundwater, nearly all of which was discharged into the city's storm drains.

At a basement project on the north end of the block, near Santa Rita Avenue, the groundwater pumping began on June 29 and concluded on Sept. 15. Here, only 133,000 gallons were pumped out. The number of gallons discharged into the storm drains? Zero.

Palo Alto generally doesn't celebrate the construction of residential basements — private amenities that have become both more commonplace and more scrutinized over the past several years. Yet for city officials, the basement at 2121 Webster St. is kind of a big deal: the first residential basement project in Palo Alto to use a cutoff wall.

A December report notes that all of the extracted water had simply soaked into the backyard.

"A typical large groundwater pumping site produces about 100 times that amount, 20 million gallons in total," the report states. "As a result, staff will convey to other applicants that this cutoff wall achieved very good results."

The 2121 Webster project may have been the city's first residential cutoff wall, but it hasn't been the only one. Two other basements have since been completed using their own cutoff walls — one at 3845 Carlson Court and another one at 1462 Edgewood Drive, a property owned by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. In each case, not a drop of groundwater went into the gutter, according to Public Works data. (By contrast, the six projects last year that used traditional basement-construction techniques discharged 115 million gallons of water into the storm drains.)

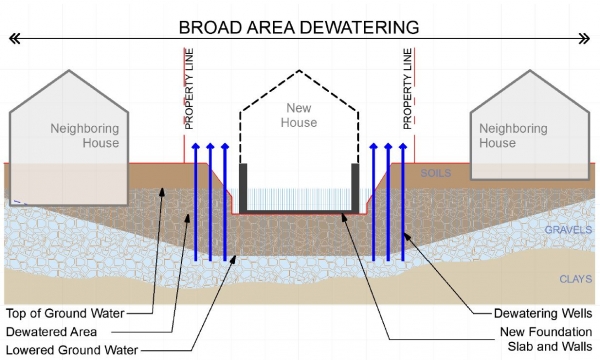

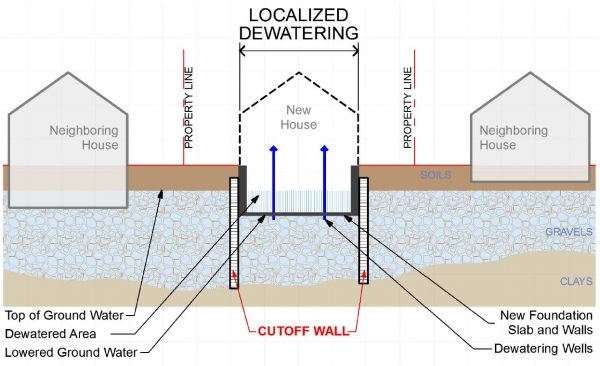

To construct a cutoff wall, builders drill a sequence of holes in the ground (in some cases, as deep as 30 feet), install I-Beams into these holes, and then fill up the space between the beams with grout, which solidifies to create a rocky curtain composed of cement and water. A basement then gets built inside the confines of this wall, obviating the need to pump water from a much broader area.

The cutoff wall technique isn't exactly new, Assistant Public Works Director Phil Bobel said. They long have been used at contaminated Superfund sites and in other areas where contractors want to restrict groundwater pumping. The 2121 Webster project was, however, the first time that such a technique was used for a residential basement in Palo Alto, Bobel said.

The use of cutoff walls in Palo Alto can be attributed in large part to a citizens group called Save Palo Alto's Groundwater, formed in 2015 to protest the growing number of dewatering projects and to promote new restrictions. Their advocacy prompted the city to gradually add requirements for projects that require groundwater pumping. Now, before dewatering occurs, applicants must complete a hydrological study that evaluates the impact of groundwater pumping on trees and neighboring properties and predicts the volume of the water drawdown. They are also required to create fill-up stations at the construction site (with strict water-pressure guidelines) so the pumped-out groundwater can be used for irrigation or construction clean-up; and to limit pumping to 10 weeks (after a two-week "start-up" period) between April 1 and Oct. 31.

Unless, that is, a builder uses a cutoff wall. As of last year, anyone who chooses this technique doesn't need to do the hydrology study, pay water-discharge fees or be subject to the strict time restrictions.

Building a cutoff wall is generally more expensive than the using the broad-based water-pumping method, but the city's requirements, such as the hydrology study, have dramatically lessened the cost differential, said Gus Carroll, whose company, Carroll Custom Homes, handled the basement project at 2121 Webster.

"If it was three years ago, it would've been much more expensive to do the cutoff walls," Carroll said. "Because we didn't have to pay any of the additional fees, the delta wasn't that dramatic."

Bobel said the goal of the city's required studies was to obtain better data about water drawdown. But the requirement also appears to have incentivized builders to pursue a wall option.

Even so, Bobel noted that cutoff walls may not always be the best approach to basement construction. Things could get problematic if the builder encounters a fluid layer, like a stream bed or gravel.

"If you were to go down and hit a layer like that, groundwater would flow under the wall very easily and it wouldn't be a good place to do a cutoff wall," Bobel said.

For that reason, Bobel said, staff has opted not to require cutoff walls — or any other specific technique — for basement construction. Rather, the city decided last month to continue to rely on its system of incentives and required studies.

That position has earned the support from Save Palo Alto Ground Water. Keith Bennett, the group's founder, called the new cutoff walls a "step in the right direction." He warned, however, that they come with their own challenges. For instance, several cutoff walls constructed in close proximity to each other could function like bricks in a bathtub.

"The disadvantage of cutoff walls is that underground construction displaces and blocks groundwater flow," Bennett said. "We see them as a good tool, but not as a one-size-fits-all solution."

It's a tool that could become even more common next year, though. Dan Garber, a local architect and former chair of the Planning and Transportation Commission, joined Bennett two years ago in exploring the feasibility of cutoff walls. Since then, Garber has partnered with Pete Moffat Construction and America Drilling, a shoring subcontractor, to create a cost model and trial methodology for using cutoff walls in residential projects. Carroll, the builder at 2121 Webster, said Garber's spreadsheet helped him arrive at the decision to use a cutoff wall.

Last month, Garber stated in a letter to the council that given the burdensome city requirements of traditional dewatering, "I do not know why any homeowner looking to build in an area of high groundwater would not pursue a cutoff wall." He told the Weekly that his group had calculated that in high-aquifer areas, the economics of doing a cutoff wall compare well with the traditional techniques particularly because the walls could cut the work time by as much as half.

Like Bennett, Garber sees the new trend as extremely promising, but both warn there is still much work to be done when it comes to limiting groundwater discharge — particularly in commercial projects.

"A single commercial project doing traditional broad-area dewatering can easily eclipse all the single-family housing projects using traditional broad-area dewatering methods," Garber wrote in an email.

Comments

Crescent Park

on Jan 12, 2018 at 11:20 am

on Jan 12, 2018 at 11:20 am

Well written and informative. Kudos.

Registered user

South of Midtown

on Jan 12, 2018 at 11:34 am

Registered user

on Jan 12, 2018 at 11:34 am

So the cutoff wall stays in place permanently? Any downsides to this?

Barron Park

on Jan 12, 2018 at 1:41 pm

on Jan 12, 2018 at 1:41 pm

This ENTIRE issue of de-watering as damaging is utter bunk.

Entirely an emotional issue having to do with old Palo Alto residents vs new Palo Alto real estate reality.

All of the arguments that shallow temporary residential de-watering somehow damages trees or adjacent properties is simply fear mongering. There is no real science involved...just vague references to non-existing terrifying conditions that result from dewatering.

Period.

Slurry cut off walls are ridiculously expensive and problematic. Requiring them is simply a means of running the construction costs up so high that it discourages basement construction. Be honest now...this is the real reason they were promoted.

Again...this is a bunch of fear mongering by those who are against a larger home replacing a smaller one. Old vs New.

Registered user

Midtown

on Jan 12, 2018 at 2:47 pm

Registered user

on Jan 12, 2018 at 2:47 pm

@Civilized Engineer: I bought my house in 1982. I replaced the toilet 3 years later. That toilet now will not hold a seal. Palo Alto Plumbing has been out twice. I have to put wood shims there or feel like I'm on a bucking bronco when seated on the toilet. Palo Alto Plumbing agreed that my house had a slope that was doubtless caused by groundwater loss.

I have three exterior doors. I had the same dead bolt locks in there all these years until about 3 years ago when four basements were dug on my street. The dead bolts were not going into the hole in the door because the house has shifted. My son had to come out and fix all these locks. I was afraid I'd eventually be locked out when the dead bolt got well and truly stuck into the wood.

I have huge cracks along where the top of a couple of walls meet the ceiling. Again, all in the past three years.

A large Chinese elm in my front yard looks very sickly and one branch looks like it's about to fall off.

This doesn't feel like fear mongering to me.

Duveneck/St. Francis

on Jan 12, 2018 at 5:19 pm

on Jan 12, 2018 at 5:19 pm

When we moved in (edge of flood zone) we were advised no basement was possible. Lo and behold, a nearby house mire in the flood zone builds one with associated tremendous de-watering. The basement square footage is not counted in the assessed value of the property, so the owners don’t pay for that. Not sure if the change in aquifer nearby is meaningful or not. Some clain meighbor trees may suffer, etc. -

Duveneck/St. Francis

on Jan 12, 2018 at 8:31 pm

on Jan 12, 2018 at 8:31 pm

Civilized Engineer <> civil engineer

Registered user

Barron Park

on Jan 13, 2018 at 9:35 am

Registered user

on Jan 13, 2018 at 9:35 am

Cracks and misaligned doors in our 92-year-old, stucco, lath-and-plaster cottage have always varied depending on the amount of rainfall. For instance, last year's rains helped close a few as the ground, and presumably the underlying water table, were seriously replenished and our aging perimeter foundation floated a bit.

This makes me think that the effects of pumping to create a basement would have the greatest impact on nearby structures -- if there was any impact. Therefore, I think any rules, regulations, incentives, etc. governing on pumping should focus on how already built structures might be affected rather than broader water table issues.

Midtown

on Jan 13, 2018 at 9:39 am

on Jan 13, 2018 at 9:39 am

Civilized engineer should visit the site on Ross Road/Colorado Ave and look at the house next door to the basement construction.You can see the obvious damage. Armchair opinion is not sufficient.

Barron Park

on Jan 13, 2018 at 10:59 am

on Jan 13, 2018 at 10:59 am

Thank you to Save PaloAlto's Groundwater and especially to Rita Vrhel for taking on this vital issue. And thank you PA Weekly for your great article on it - good job Gennady. The chart was alone worth 1000 words as it compared the approximate 100 million gallons of water of wasted water pumped from just 6 developments that was dumped into our storm drains, compared to 3 developments that used cutoff walls - zero gallons discharged and wasted. Now the City must, in its policies and practices, be assiduous in perfecting saving and recycling our water.

Take a bow - you water savers have served your City and residents well. You are an example of what all of us can do when we organize around an issue that needs to be addressed. We don't need to wait for someone else to show leadership, or hope the right person gets elected, or the staff will notice. We each can lead and we all can work together on issues that matter to us to make our city better.

Downtown North

on Jan 13, 2018 at 12:52 pm

on Jan 13, 2018 at 12:52 pm

"Slurry cut off walls are ridiculously expensive and problematic. Requiring them is simply a means of running the construction costs up so high that it discourages basement construction."

Anybody who can afford to buy and clearcut a perfectly good house to build a macmansion can easily afford to protect their investment with a slurry wall.

Has Civilized Engineer ever calculated the buoyancy force lifting a basement surrounded by water? Do it on a per square foot basis for a range of submergence depths. Show your work.

Old Palo Alto

on Jan 13, 2018 at 10:13 pm

on Jan 13, 2018 at 10:13 pm

Wonderful. The tinfoil hat crowd is afraid of water sprites, and has convinced government to add regulations to jack the cost of building.

It’s like a stupid tax that everyone else pays.

Wonderful.

Old Palo Alto

on Jan 14, 2018 at 12:42 pm

on Jan 14, 2018 at 12:42 pm

Winter-

you are absolutely right: the success that savepaloaltoground.org has had is directly tied to Rita Vrhel and Esther Nigenda's tenacious, persistent organizational and research skills. They were part of savepaloaltoground.org long before I was. Their untiring and inclusive approach to community engagement is inspiring.

Another Palo Alto neighborhood

on Jan 16, 2018 at 9:30 pm

on Jan 16, 2018 at 9:30 pm

Corrected URL: Web Link

Palo Alto High School

on Jan 16, 2018 at 9:49 pm

on Jan 16, 2018 at 9:49 pm

@Civilized Engineer -- If you remove 22 million gallons of water from the soil -- equivalent to 1000 swimming pools of water (just imagine that) -- it will definitely have an impact on the soil under nearby homes. It's just a debate over how much impact, and what you can get away with.

Another Palo Alto neighborhood

on Jan 17, 2018 at 10:48 am

on Jan 17, 2018 at 10:48 am

Maybe I missed it, but, I didn't see in the article or discussion any actual costs. Just how "ridiculously expensive" additional cost are we talking about for a cutoff-wall for a, let's say, 1000 (2000, 3000, pick some numbers) square foot basement?

another community

on Jan 25, 2018 at 9:37 am

on Jan 25, 2018 at 9:37 am

From an engineering perspective it seems the general residential distress reported by others commenting here is very typical of seasonal expansive soil movement which is endemic to the area- this should not be confused with localized drawdown of the water table around a basement. The regional water level has been fluctuating for hundreds of thousands of years... Also, dewatering does remove water locally, but it goes right back into the water cycle via the City storm drain- this really does not remove water from the system as a whole. And if the noted residential distress IS due to the expansive soils, then it is interesting to note the drawdown in a clayey soil will be limited and will occur closer to the excavation (versus in a sandy soil where the water table can be drawn down farther away from the excavation). So if it's expansive soils causing your distress, then the chance of the dewatering from a basement excavation in the neighborhood impacting the water table on your property would be less.

Cut-off walls can be very effective, but there is still a need to dewater within the excavation and there can be water intrusion from outside the wall too depending on geologic conditions.